Literacy in the Math Classroom: Vocabulary

Literacy in the Math Classroom: Vocabulary

Looking for a way to spice up a review day? Students in Geometry reviewed for a quiz by playing a version of Taboo. First round, they pull a slip of paper with a vocabulary term on it and then they must describe to their teammates the concept without using the term itself. Students describe theorems, angles, scale factor, and more in their race against the clock and in their competition against another team. Round 2 presented students with the challenge of creating drawings of their vocabulary words, and students busily sketched alternate interior angles, corresponding angles, and other related terms to clarify their thinking, making plain any misconceptions to their teacher. Learning vocabulary can be a fun process!

Literacy in the Math Classroom: Speaking and Listening

Tired of the sound of the same three voices in your classroom? In a Geometry classroom near you, students partnered up based on the shape of their assigned polygon and then discussed which statements posted around the room were true or false for their image. Choosing to group students by partners filled the classroom with different voices and required all students to make meaning of key terms, like similar, congruent, and isosceles. Getting more students talking gets more students learning.

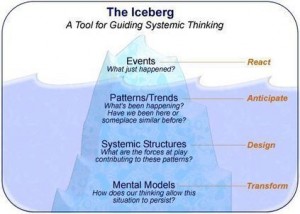

Literacy in the Science Classroom: Reading

Whether students are reading a text or a word problem, some don’t know the questions good readers ask themselves during the process. A Chemistry teacher recently modeled her own think-alouds as she tackled a word problem with her students. By sharing her thinking and delineating the questions she asked herself throughout the process, the teacher was able to help students begin to own the process of breaking down a complex text.

Whether students are reading a text or a word problem, some don’t know the questions good readers ask themselves during the process. A Chemistry teacher recently modeled her own think-alouds as she tackled a word problem with her students. By sharing her thinking and delineating the questions she asked herself throughout the process, the teacher was able to help students begin to own the process of breaking down a complex text.

What do literacy strategies look like in your classrooms and content areas?

Mandy Melton asks her students to learn a concept (like

Mandy Melton asks her students to learn a concept (like