As Kirkwood School District Instructional Coaches and facilitators, we often play many roles: mentor, data coach, lead learner, and curriculum specialist, just to name a few. We support the district mission “to develop students who will add value to our dynamic world using knowledge, character, and problem solving skills” and believe we are a part of making the district vision a reality where “we will succeed when all our students and graduates:

- take an active role in improving our community

- seek to understand and communicate multiple perspectives or points of view

- act in ways that promote physical, mental, and emotional health

- communicate effectively about a wide range of topics with a diverse audience

- participate in designing and making decisions about their learning

- have the knowledge and skills necessary to succeed beyond graduation”

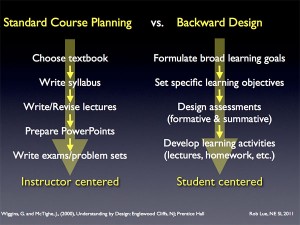

In our work in the district with Understanding by Design for the past 3 years, many of us have lent our expertise in helping teachers think through their big ideas, enduring understandings, essential questions, learning goals, and the learning design to help students not only attain the skills and content knowledge they need to succeed in one course, but to transfer that understanding across grade levels and disciplines.

Coaching & the Strategic Plan

In continuing to support the mission and the vision, the focus to our work becomes more clear in Kirkwood School District’s new Strategic Plan. The first Focus Area in the Strategic Plan is High Quality Instruction Leading to Student Achievement. Within this focus area, there are 3 main goals:

- We will implement high quality, research-based instructional practices in every learning environment.

- All students will be engaged in meaningful learning experiences that foster depth of knowledge and cross grade levels, disciplines, school buildings, and extend communities.

- Students will be prepared and empowered to transfer their knowledge and skills through collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and creative problem solving as citizens of the global community.

As Instructional Coaches, we have an opportunity to support the thinking and learning around these goals and to help teachers, students, and administrators consider ways to assess our success in attaining those goals. More specifically, KSD’s Strategic Plan calls for “data measures for all goals leading to high quality instruction,” and lists “common assessments, rubrics and grades, and use of feedback by students and teachers” as ways we can measure our success.

We are part of the action plan, where we support/create “a system for high quality professional development that provides many learning opportunities and combines a variety of learning strategies and resources so teachers and administrators develop the knowledge, skills, practices, and dispositions they need to implement high quality, research-based instructional practices in every learning environment, engage students in meaningful ways, and prepare and empower students to transfer their knowledge, skills, and understanding.”

Coaching & Needs Assessment

While the strategic plan lists common assessments as one measure of our goals leading to high quality instruction, we coaches might find teachers and administrators are interested in beginning with a broader vision of assessment before designing specific assessments. One tool that may help our schools think through their own assessment literacy is adapted from UNC Greensboro’s SERVE Center, and asks educators to gauge their expertise as an assessment literate teacher. Teachers rank their proficiency in

- defining clear learning goals

- making use of a variety of assessment methods to gather evidence

- analyzing achievement data

- making good inferences from the data gathered

- providing appropriate feedback to students

- making appropriate instructional modifications

- involving students in self-assessment

- engineering a classroom environment that boosts student motivation to learn

Once coaches have an idea of the needs represented by their staff from this pre-assessment, they can begin to compile resources, provide professional learning opportunities, and support teachers through one-on-one or small group coaching conversations. The beginning of those supports has been gathered here, and some additional supports are available on the district facilitators page.

Coaching & Defining Clear Learning Goals

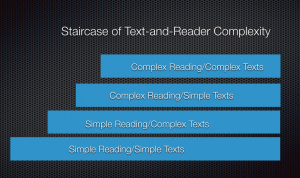

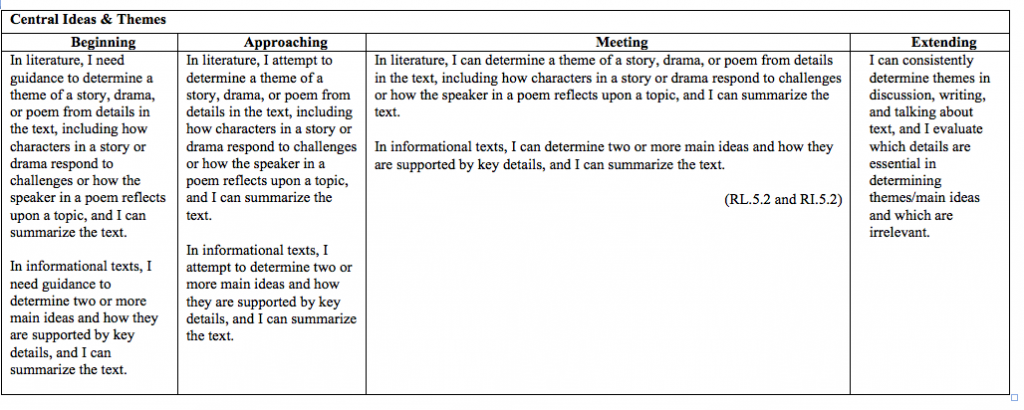

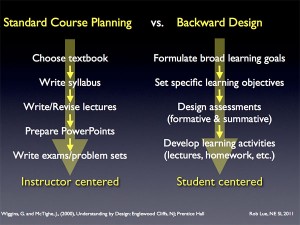

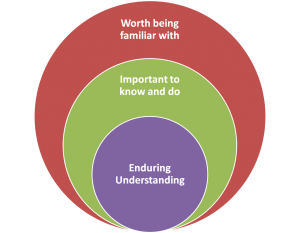

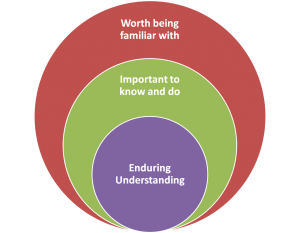

Teachers who need support in defining clear learning goals might not yet be able to articulate what they want students to know and be able to do, how their goals align with new national standards, or how to make plain the daily learning targets for students while holding larger transfer goals in mind as well. Creating high quality assessments without this clarity is next to impossible, so beginning with building their capacity to craft learning goals for different purposes is a powerful first step.

You might begin with supporting teachers as they think through their transfer goals for students. These overarching goals will help  to frame the other learning they want students to engage in throughout their course as well. Teachers can connect with coaches to better understand how transfer goals inform their meaning making goals as well as the acquisition goals they have for their students.

to frame the other learning they want students to engage in throughout their course as well. Teachers can connect with coaches to better understand how transfer goals inform their meaning making goals as well as the acquisition goals they have for their students.

Coaching & Making Use of a Variety of Assessment Methods to Gather Evidence

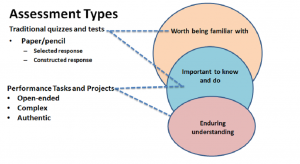

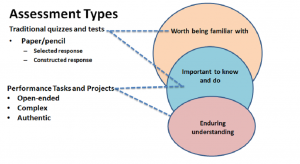

Once teachers have a richer understanding of what they want their students to know and be able to do, they need to determine the acceptable evidence of that understanding. In our district, many schools are working toward common assessments as one of those pieces of evidence, yet formative assessment and teacher observation are also key in understanding the whole child.

For teachers new to Kirkwood, new to teaching, or new to the idea of multiple measures, coaches might engage in an article study on “The Many Meanings of Multiple Measures” by Susan Brookhart. Teachers wanting a thinking partner about how assessment informs instruction might converse with a coach about Carol Ann Tomlinson’s “Learning to Love Assessment.” Once the theoretical reasoning is solid, teachers might need support in the day to day use of assessment and how it should impact their instructional response. Attending conferences, like Differentiation and the Brain with Tomlinson and Sousa will provide opportunities to test their classroom application theories with people from within and outside the district. Teachers will walk away from these conferences with tools and notes in hand, ready to adapt their learning to meet the needs of their students.

As teachers begin to craft their common assessments, assessment blueprint tools will help them insure their assessment is aligned to their big ideas and learning goals and that it provides more than one opportunity for students to demonstrate their level of mastery. For teachers who inherited common assessments or who would like to look at their own assessments with a more critical lens, Wiggins and McTighe’s Two-Question Validity Assessment might prove useful.

As teachers begin to craft their common assessments, assessment blueprint tools will help them insure their assessment is aligned to their big ideas and learning goals and that it provides more than one opportunity for students to demonstrate their level of mastery. For teachers who inherited common assessments or who would like to look at their own assessments with a more critical lens, Wiggins and McTighe’s Two-Question Validity Assessment might prove useful.

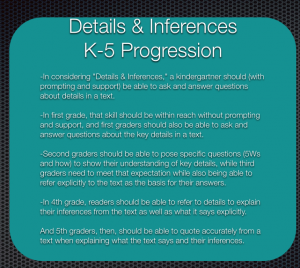

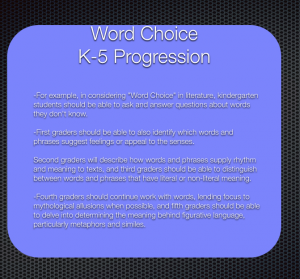

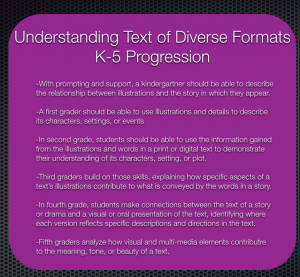

Coaching & Analyzing Achievement Data & Making Inferences

With so many different forms of data to analyze, teachers may identify data analysis as one of their coaching needs. Whether the teacher is working alone or in a Professional Learning Community, understanding the questions to ask when looking at data are perhaps as important as the data itself. Luckily, the National School Reform Faculty has compiled a variety of protocols for data analysis that are ready-to-use but can also be easily adapted to fit the timeframe of your data meetings.

One protocol that is particularly useful when working with teachers new to data analysis is “Data Driven Dialogue.” In this protocol,  coaches help teachers surface their perspectives, beliefs, and predictions about the data before moving on to analyzing the data for patterns and inferring or planning new actions as a result of the data. The ATLAS protocol serves coaches well when there is a limited amount of time for data analysis and a goal is building capacity of other teacher leaders to lead data meetings. The steps, timeline, and questions are clearly delineated for teachers and coaches new to leading data team meetings.

coaches help teachers surface their perspectives, beliefs, and predictions about the data before moving on to analyzing the data for patterns and inferring or planning new actions as a result of the data. The ATLAS protocol serves coaches well when there is a limited amount of time for data analysis and a goal is building capacity of other teacher leaders to lead data meetings. The steps, timeline, and questions are clearly delineated for teachers and coaches new to leading data team meetings.

When teachers examine two data sets, specifically observational data, the Data Mining Protocol may be used. In looking at student work across classrooms and grade levels, the Interrogating the Slice Protocol keeps teachers focused on student work and the patterns and insights that emerge from the data, suggestive of an instructional response.

Finally, your teachers may ask for support in using the Ferguson-Florissant data site and making sense of the data available to them within their classrooms, their courses, their grade levels, and their schools. A step-by-step guide that I used with freshman and sophomore English teachers includes screen shots and instructions for accessing the data on this site, which reports might be most fruitful for individual and course-level reflections, as well as a protocol for thinking through data, and resources to consider for planning the instructional response to the data.

Coaching & Providing Appropriate Feedback to Students

After the assessments have been given, teachers will also need to provide feedback to their students, and both veteran and new teachers alike might find tools in these articles to sharpen the impact their feedback has on student achievement. These articles would be interesting for coaches to use as they lead a close reading activity prior to digging into common grading of assessments or even individual teachers completing their own grading.

In Goodwin and Miller’s article, they point out that much research suggests the feedback we often give as teachers (a score or percentage) actually has negative effects on learning. Instead, we should focus our efforts on written feedback that is linked to objectives, timely (sometimes immediate, sometimes delayed, depending on the kind of learning desired), and specific. How many times did I write the comment vague on a student’s paper only to discover weeks later that he had no idea what that word meant and no idea how to correct the issue, even when he had learned the definition?

In Goodwin and Miller’s article, they point out that much research suggests the feedback we often give as teachers (a score or percentage) actually has negative effects on learning. Instead, we should focus our efforts on written feedback that is linked to objectives, timely (sometimes immediate, sometimes delayed, depending on the kind of learning desired), and specific. How many times did I write the comment vague on a student’s paper only to discover weeks later that he had no idea what that word meant and no idea how to correct the issue, even when he had learned the definition?

Fisher and Frey echo these themes in “Feed Up, Back, Forward,” where they describe feedback as feeding up (clarifying the learning goal), feeding back (providing information to students on where they are in relation to the goal and what steps they need to take next), and feeding forward (data informing their next instructional choices to improve learning.)

Coaching & Making Appropriate Instructional Modifications

As teachers plot their next steps in teaching, coaches can play a pivotal role in helping them focus their efforts on the strategies proven to be most effective. Whether it is selecting strategies from Hattie’s list of greatest impacts on student achievement to adopt and adapt or focusing on Marzano’s High Yield Instructional Strategies, teachers benefit from coaches sharing the suggested strategies and the conversation that precedes and follows examining the list.

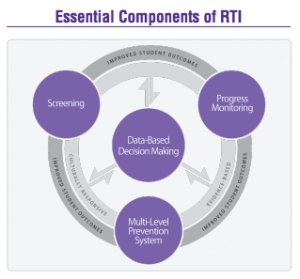

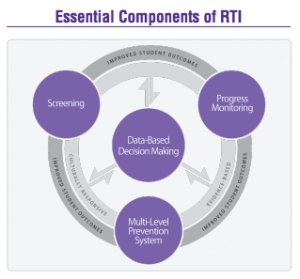

Teachers contemplating their instructional choices might engage a coach in further exploring the models of Response to Intervention (RTI) or Differentiated Instruction to improve students engagement and achievement. Still others might notice a lag in their students from families with lower socioeconomic status, and a coach could provide Jensen’s text on poverty’s effect on the brain or other articles, like Payne’s, on the instructional response to poverty as first steps toward awareness and designing learning to help bridge the existing gaps for those students.

the models of Response to Intervention (RTI) or Differentiated Instruction to improve students engagement and achievement. Still others might notice a lag in their students from families with lower socioeconomic status, and a coach could provide Jensen’s text on poverty’s effect on the brain or other articles, like Payne’s, on the instructional response to poverty as first steps toward awareness and designing learning to help bridge the existing gaps for those students.

Coaching & Involving Students in Self-assessment

While teachers make instructional choices based on the data they receive from their assessments, students should also be gauging their success in hitting the learning targets and tracking those patterns of achievement over time. This practice can seem overwhelming to teachers who are just beginning to use assessment results for their own planning, and a coach can guide teachers in choosing the bite-sized chunk they are willing to engage their students in for self-assessment. Pickering and Marzano have exemplars readily available for adaptation.

Coaching & Engineering a Classroom Environment that Boosts Student Motivation to Learn

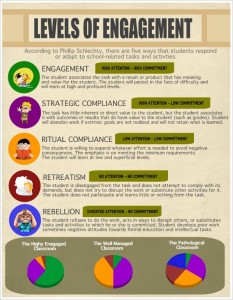

While all of the learning listed above should lead to greater engagement on the part of students, sometimes teachers will engage a coach with a class whose sluggish data on student achievement mirrors the level of student engagement. Much of the work of the coach is in listening, observing, and gathering data in these instances, but occasionally, a teacher might seek out a new strategy or two to try as well.

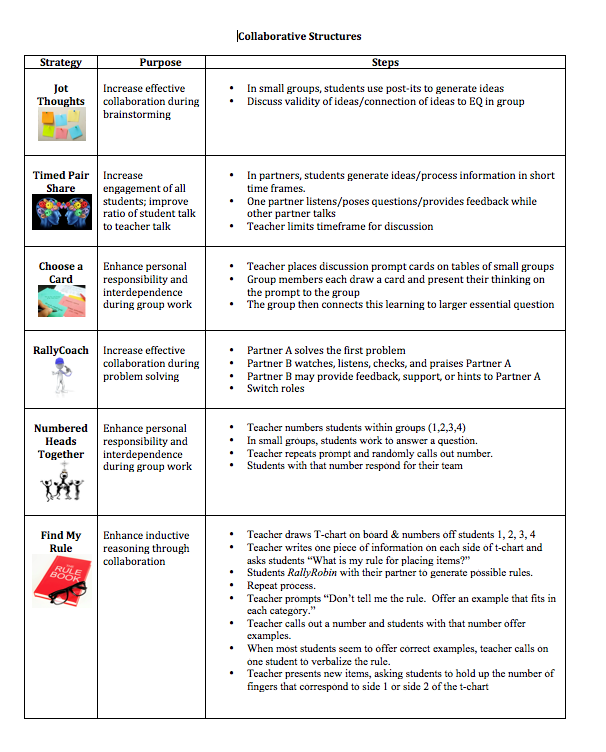

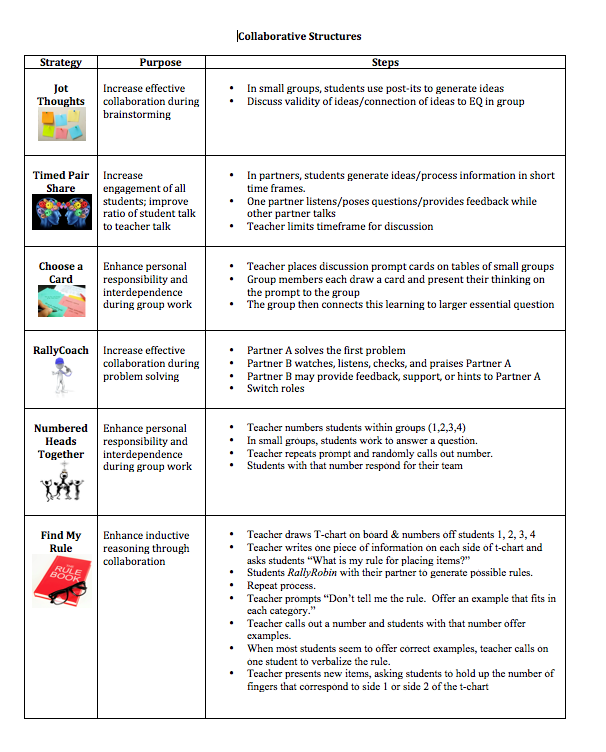

Dr. Spencer Kagan’s collaborative structures offer ways to boost student engagement through their focus on four essential qualities. Some of the structures listed above might be a the just-right step teachers are ready to take in rethinking student engagement.

Dr. Spencer Kagan’s collaborative structures offer ways to boost student engagement through their focus on four essential qualities. Some of the structures listed above might be a the just-right step teachers are ready to take in rethinking student engagement.

Coaching & Assessment Literacy

Coaches provide the job-embedded, on-site, just-in-time professional learning research suggests has the greatest impact on supporting teacher growth. Our work with teachers begins with the end in mind: “to develop students who will add value to our dynamic world using knowledge, character, and problem solving skills.”